If you haven’t heard of two-way electricity tariffs, don’t worry. It’s a relatively new concept that’s only recently been trialled in NSW and won’t be widely implemented for at least another 12 months.

However, if you have a solar-powered household or small business – or are considering getting a rooftop PV system in the future – it’s good to know what two-way tariffs are.

Four Australian energy distributors have introduced a two-way tariff this past month, so there are already some solar homeowners seeing them in action.

The changing energy generation dynamic

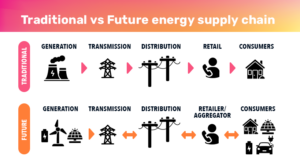

Back in the old days, generators generated, distributors distributed, retailers sold, and consumers consumed. It was a simple supply chain that flowed one way, from the generator to the end user.

That’s all changed now that so many consumers are also generators. Anyone with a solar system that can feed excess energy back into ‘the grid’ can be either the start or the end of the new supply chain.

Rooftop solar has completely changed the entire energy landscape

Because our wide brown land is a prime candidate for the localised collection and use of the energy of the sun, Australia has the highest penetration of rooftop solar in the world.

That’s been encouraged and incentivised, via various government rebates, and there are plenty of households loving every bit of their new rooftop-mounted energy freedom.

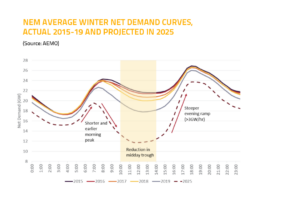

However, there have been consequences, not least the duck curve. This graph shows what happens when we see a lot of solar-generated energy available in the middle of the day: the demand for energy generated by other sources goes from minimal at that time to substantial when the sun goes down.

There are now three different types of household energy consumers

Because not everyone has rooftop solar, and those with a solar system may or may not have battery storage (not to mention that some have electric vehicles), usage and demand patterns are now far more varied from consumer to consumer.

If you have rooftop solar with battery storage, you don’t have to worry too much about what happens to any excess energy you generate. You also don’t have to worry about spikes and troughs in demand and how that might impact the cost of electricity to the rest of the community.

If you have rooftop solar but no battery, you might think about using more electricity during daylight hours, when you’re generating your own. But then you might also just switch on whatever appliances you want after the sun goes down without worrying too much about how that’s being generated or supplied.

So, with some households meeting their own energy needs, others generating a portion of what they need but still using the grid for the rest (at the same time as everyone else), and a whole lot of others without solar relying entirely on the grid, the system has become more complex, less predictable, and more inequitable.

Two-way tariffs offer an incentive to help address the duck curve

As part of the incentive to make it more attractive for people to install rooftop solar, those who set up their system to be ‘export capable’ were offered feed-in tariffs. These rebates paid those new energy generators for the energy they exported (distributed back to the grid) for others to use.

However, the value of that excess energy has greatly diminished over the past few years. Of course, when it was helping to meet a demand, it was quite valuable. Now that it’s contributing to an oversupply, some of it is worse than worthless during the middle of the day, because at that time some of that excess has nowhere to go, but it still needs to be ‘managed’.

The concept of the two-way tariff has modified the incentive to make it suit the current supply-demand environment. There’s a point where an export-capable household will be penalised for contributing to the oversupply, balanced by a greater incentive to export energy back to the grid at times it can be used.

How do two-way tariffs work?

Two-way tariffs are essentially time-based incentives (and disincentives) to encourage rooftop solar owners to export their excess energy when it’s needed rather than when it’s not.

In some ways, this makes those who generate electricity via the solar system in their home or small business more aligned with that role within the supply chain, a generator who makes money by supplying energy when it’s needed.

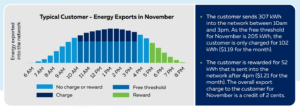

As the below Ausgrid diagram illustrates, there is no charge or reward for exporting a certain amount of energy at certain times of the day. However, between 10 am and 3 pm, if the amount a consumer exports is above the free threshold, they will be charged to cover the cost of managing that excess amount during that period when there is more energy from rooftop solar than can be used.

Then, if the household exports any excess energy after 5 pm, they will be paid for that valuable contribution to our collective energy needs.

These changes are intended to encourage more renewable energy

With the outstanding adoption of rooftop solar came a problem. Some areas reached capacity for exports back to the grid, meaning people installing new solar systems had to be restricted from exporting. This, naturally, made going solar less attractive.

As a result, regulators made a change that required networks to invest more to allow at least some level of export. At the same time, pricing frameworks were amended to ensure that the cost of any new infrastructure needed to allow greater export was passed on to the customers whose exporting was driving the need for that investment.

By removing constraints on the network, while creating better incentives for households to export their excess energy outside the middle-of-the-day peak, these changes should make investing in rooftop solar remain viable for more consumers.

Because of the incentive to ‘time shift’, two-way tariffs might also make it more attractive for people to include battery storage with their solar installation.

What will two-way tariffs mean in dollar terms?

Based on the Ausgrid ‘Typical Customer’ diagram above, it’s anticipated that the two-way tariff will have a negligible impact on the electricity bills of most exporting customers.

Ausgrid explains that “a typical 5 kW solar customer will see an annual bill increase of $6.60 per year. This includes $13.30 a year of charges offset by $6.70 of export rebate”.

However, that ‘typical customer’ is based on those who don’t do anything to take advantage of the new incentives.

A participant in one of the trials consciously changed his behaviour and usage patterns and found he could make a ‘profit’ of between $2 and $6 every day simply by using as much of his energy as possible during the day and storing most of his excess in his Tesla Powerwall 2 battery, then exporting from that when the ‘reward’ tariff was on offer.

He even managed to score “the odd $20 day when there’s a wholesale spike”.

When will two-way tariffs be the norm?

Two-way network tariffs will officially be introduced from July 2025.

However, distribution network companies are allowed to run carefully monitored two-way tariff trials now, as part of the 2019-2024 regulatory period.

When the Australian Energy Market Commission agreed to update the national energy market and retail rules to accommodate the two-way flow of electricity (a decision made in 2021 after much debate) it included several consumer safety mechanisms, such as opt-in clauses.

There’s more to be learned from the trials and GloBird Energy (like all retailers) will need to work out how we adapt to whatever becomes the new normal.

One thing that seems to be clear though is that batteries are starting to make more sense. If you can control when and how you use energy, or when you export energy, it’s likely you’ll gain as the market starts to recognise and reward you for providing your energy at times when it’s most valuable.