You might have seen the big headline from the 28th conference of the parties – COP28 for short – in the United Arab Emirates, that Australia has joined more than 100 other countries across the globe in committing to a tripling of renewable energy capacity by the end of the decade.

Perhaps the idea was to make us all sit up and take notice, but tripling sounds like it’s asking a lot. It would be adding an amount of renewable energy that would be enough to power the entire United States each year for the next seven years.

If the world wasn’t already trying hard to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels and to ramp up renewables, perhaps tripling from a lower starting point would be an understandable goal.

The issue is that, with a lot of renewable energy projects already committed to between now and 2030, it’s hard to see where a lot more is going to come from.

11 terawatts really is a lot

This Global Renewable Pledge wants countries to commit to increasing renewable energy generation capacity to at least 11 TW – that’s 11 million megawatts.

Right now, the world can call on around 2.3 TW of total installed capacity for wind and solar (by far the main contributors to the renewable energy pool), so the announced renewables target will require an unprecedented acceleration in deployment.

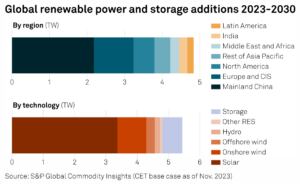

According to analysis by S&P Global Commodity Insights, some 4.6 TW of solar and wind capacity are forecast to be added between now and 2030, at a cost of $4.7 trillion.

So, the existing 2.3 TW plus the forecast 4.6 TW would leave us around 4 TW short of that proposed target of 11 TW by 2030.

“The Commodity Insights scenarios indicate that this is an ambitious target. Despite the significant increase in renewable deployment by 2030, installed capacity only doubles in our base case,” said Anna Mosby, Head of Environmental Policy Analytics at S&P Global.

We’re already making a lot of progress

While some countries might be slower to make progress than others, globally there’s no denying that renewable energy projects are being conceived, approved, financed, and delivered.

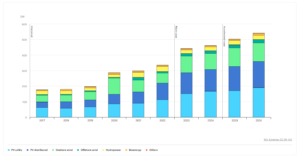

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Renewable Energy Market Update of June 2023 stated that “Global renewable capacity additions are set to soar by 107 gigawatts (GW), the largest absolute increase ever, to more than 440 GW in 2023”, noting that amount was equivalent to more than the entire installed power capacity of Germany and Spain combined.

The IEA also pointed out that “Multiple countries in Europe including Spain, Germany and Ireland will see wind and solar PV’s combined share of their overall annual electricity generation rise above 40% by 2024.”.

For reference, here’s the IEA’s chart of Net renewable electricity capacity additions by technology, 2017-2024

Australia says it’s on board

The Australian government is embracing almost everything that COP28 is tabling (with the notable exception of nuclear energy), however, concerns remain that no matter how upbeat we might want to be about “leading the world” we might not even be able to meet our previous levels of commitment.

Only days before the conference started, the government had to rewrite the blueprint for its own domestic target amid concerns the country would fall short.

Late last month the government outlined plans to use taxpayer subsidies through its “capacity investment scheme” to underwrite renewable energy projects and the so-called firming capacity, such as battery storage, that would be needed to back them up.

So, the big question remains whether governments and companies will effectively rally the huge investments needed to hit the “ambitious” goal.

While the number of clean energy deployments, including solar and wind power projects, has surged over the past several years, rising prices for materials, labour constraints, and supply chain disruptions have forced project delays and cancellations in recent months.

Investment analysts are far less optimistic

Governments and international talkfests can be as ambitious and optimistic as they like, but the bottom line is that the money has to come from somewhere.

In the end, talk is cheap, but renewable energy projects and the accompanying infrastructure are not.

Schroders’ Head of Australian Equities Martin Conlon believes that expectations that Australia’s energy providers will invest aggressively in renewables are far too optimistic.

While he acknowledges that the world has accepted the need to build more renewable energy infrastructure, he contends that energy providers do not have the profit pools (or incentives) to pay for them.

“I think that the problem with the current level of electricity prices globally is that there’s not a big enough profit pool to pay for the trillions of investment [needed to transition],” Conlon told Livewire Markets, adding that most renewable energy investments globally struggle to make money.

“The idea that the government can expect a huge amount of money to come in to build renewable energy in the envelope of current electricity prices, to us, is just unrealistic.

“There’s a cost of renewable energy and the profit needs to come from somewhere.”

Let’s hope all this doesn’t push energy prices upward because, although consumers support more renewable energy, they also rely on affordable reliable energy.

Our hope is that new technologies are the answer. On this blog, we keep track of any new and exciting technology that’s coming online, and the good news is that there is plenty of work being done in this space.