When you think about solar energy, you’re probably picturing a bank of photovoltaic (PV) cells, possibly on a roof, that convert sunlight directly into electricity.

That wouldn’t be surprising, considering that Australia leads the world in the penetration of rooftop solar, with about one in five houses now having an array installed.

In 2001, only 118 Australian homes had solar panels installed. In March 2013, that number passed one million and late last year we topped the 2 million.

But it takes more than rooftop installations to get the capacity of solar energy generation the world is looking for.

What’s happening around the world?

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), solar PV capacity generated around 2 per cent of global power output (398 gigawatts) in 2017.

When Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables analysed the global data in 2017, they forecast that solar energy production would more than double to 871 gigawatts by 2022.

Only a year later, last August, they found everything pointing to higher-than-expected growth, and they now anticipate that the world will have one trillion watts – or one terawatt – of solar capacity installed by 2023.

China, India, and Japan will account for 20 per cent of that capacity.

Meanwhile, last November, the IEA released its 2018 World Energy Outlook and the agency – which, by the way, is generally accused of being too conservative in its predictions about renewable energy – modelled four possible future scenarios, each of which saw solar PV capacity overtaking all other forms of energy, apart from gas, by 2040.

How are we getting there?

More and more countries are building large-scale solar farms, with India and China setting the benchmarks.

Two years ago, China’s Longyangxia Dam Solar Park was the biggest, with 4 million solar panels covering more than 25 square kilometres and a capacity of 850 megawatts.

It generates around 220 gigawatt-hours of electricity per year, which is the equivalent of powering 200,000 households.

India has since topped that with the Kurnool Ultra Mega Solar Park offering 1000 megawatts of generation capacity and is about to double that with the 2000-megawatt Shakti Sthala, which spans over 50 square kilometres. When completed it will provide enough electricity to power around 700,000 homes!

Here in Australia, we might not have projects anywhere near that capacity, but the number of solar farms being built is pretty impressive.

The Clean Energy Council, which tracks renewable energy projects, tells us that 25 large-scale solar plants were completed in 2018 – including the six largest in the country – and that a further 60 are either under construction or due to start soon.

The biggest right now is at Port Augusta in South Australia (220 MW), however, Balranald – which is just over the Victoria-NSW border, about 100km north of Swan Hill – is set to become the home of Australia’s two biggest solar farms, one with a 255-megawatt capacity and the other generating 349 megawatts.

And so … how do we rank?

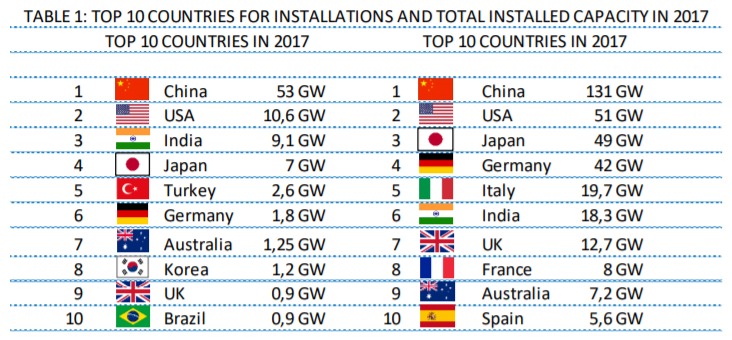

The most recent report from the IEA, 2018 Snapshot of global photovoltaic markets (you can download the 16-page report here), ranks Australia 9th for total installed PV capacity.

We were also 7th for the capacity installed in 2017 – so, considering there were only a handful of new large-scale projects that came online in 2017 compared to those 25 in 2018, we might even be further up that list now.

Here’s the table from that IEA report, with China out to a clear lead, with the USA, Japan, and Germany close together, but way behind China:

It’s also worth noting what percentage of the total energy consumption of each country the solar capacity represents.

China’s solar generation represents just 1.8% of their total consumption, the US is a little higher at 2%, Japan’s is up at 5.9%, while Germany (7.5%) and Italy (7.7%) are the world leaders on that measure.

Australia is somewhere in the middle, with our solar generation capacity representing around 3.8% of our total energy consumption.

It will be very interesting to see how those figures change over the next five years, as the world heads toward that predicted benchmark of one terawatt.