We’ve posted previously about the role that ‘the grid’ plays in distributing electricity up and down the east coast of Australia.

Most of the millions of homes and businesses in Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania, New South Wales, the ACT, and Queensland are connected to the national electricity network, and we rely on it to get the electricity to us.

A large portion of every electricity bill is to cover network costs, basically the cost of building, managing, and maintaining the infrastructure (often referred to as ‘poles and wires’) that distributes electricity from the generators to customers.

In our recent post Is it unrealistic to expect no blackouts?, we explained how a failure of infrastructure in South America blacked out most of Argentina and Uruguay in June, leaving 48 million people without power.

On a very different life-and-death level, powerline faults caused 159 of the 173 deaths and were responsible for an estimated $4.4 billion worth of damage during Victoria’s Black Saturday fires of February 2009.

So, there can be no dispute that having a robust, efficient, reliable, and safe grid is paramount.

Don’t we have the infrastructure we need?

This is a multibillion-dollar question – literally – and there’s no simple answer.

The grid might be pretty good, but it was designed and built when the majority of electricity was generated in particular ways in particular locations, before being distributed to where the majority of people lived.

Times are changing, with new sources of power generation in new places, and ever-increasing demand both in the major population centres and further away, as new developments contribute to urban sprawl.

Not to mention technological advances, such as the rapid earth fault current limiters being implemented across Victoria in an attempt to prevent anything like Black Friday happening again (as we’ve noted previously, the project was initially expected to cost Victorians $151 million but has now blown out to an estimated $540 million).

Hence the sizeable proportion of our bills being attributed to network costs.

Does that explain why they keep going up?

Perhaps this is the bigger question. Let’s make up an arbitrary number, say $500 million. If that was the annual network cost distributed evenly across five million customers, each customer would be charged $100 dollars a year.

If it increased by 10 per cent each year – keeping in mind the number of customers also increases by some lesser percentage – the following year’s $550 million cost might be divided amongst more than five million customers, so each customer might pay $108 dollars that following year.

Of course, those aren’t real or even indicative figures. We just wanted to give you a feel for the reality that slight increases year-on-year are probably to be expected.

In the past, the businesses that own this infrastructure have faced lawsuits when things go wrong. For example, AusNet Services was forced to pay out $500 million in 2014 over the 2009 Victorian bushfires.

So, it’s no surprise that they’ve done a lot of work in recent years building and maintaining the network. It’s an ongoing process which does cost money, and that spending is passed on in the form of increased charges.

It’s difficult to know how much spending is needed to maintain the network at its absolute optimum. At what point is the infrastructure exactly as good as it should be, not better or worse? There has to be a sweet spot between overspending while gaining a relatively small increase in reliability and underspending at the expense of safety.

There’s also the consideration of returns for the owners of these assets and their shareholders.

Because there are so many factors to consider, the network companies must present their case to the regulators to get approval for the cost increase everyday energy customers will ultimately end up paying.

So, are network charges going up again?

In early November, the Australian Energy Regulator gave the go-ahead for electricity distributors to increase network charges from January 1 by up to $53 for a typical household and $212 for typical small businesses (the exact amount depends on which zone you’re in and how much power you use).

The AER cited the cost of transmission and land taxes as the key reason for the price hikes, which will cost Victorians an extra $98 million in network charges in 2020.

The Victorian opposition points out that the tax component is an example of the State government indirectly taxing all Victorians, because the AER has little choice but to recognise that as part of the real cost of doing business and approve the extra charges being passed on.

Retailers then also have no choice but to pass on those regulated costs to customers.

Unfortunately, the increase is industry-wide, so there’s no way of avoiding it.

Is the grid going to be better as a result of this significant additional cost?

That’s hard to say. The Victorian opposition is yet to be convinced that anything that forces your bills higher can be justified in the current climate of households under real financial stress.

We can certainly see their point although, at the same time, the state government makes the point that infrastructure spending is necessary, and a stable grid is important.

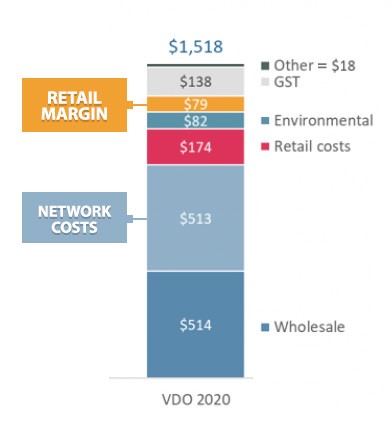

Below is a graphic taken from the Essential Services Commission website about a typical energy bill, and how much is made up by network costs, wholesale costs, and the average retail margin:

The bottom line is that while network costs are necessary and unavoidable, we want to feel as if every segment that contributes to your bill is being managed prudently and the businesses involved are trying to find efficiencies to lower costs.

Otherwise, no matter what politicians say about ‘downward pressure on prices’, we will keep seeing energy bills going up.