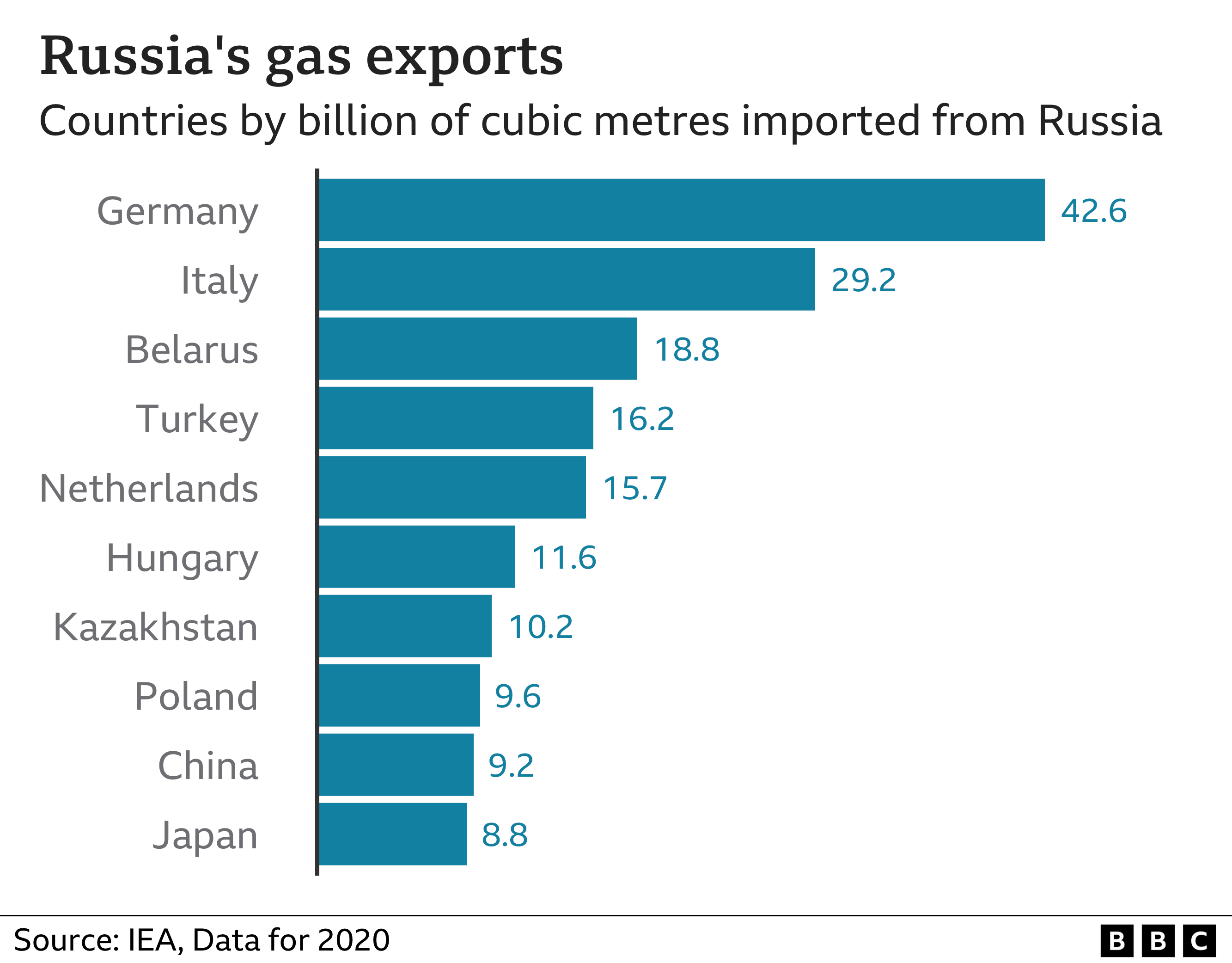

Right now, much of the European Union (EU) is scrambling to locate and secure alternative energy supplies to one of its main long-term sources, Russian gas.

Last year, around 40 per cent of Europe’s gas supply, some 155 billion cubic metres (BCM), came from Russia.

As you can see in this graph (thanks to the BBC), Germany and Italy are particularly reliant on gas from Russia:

Energy prices in Europe are already considered high – in some cases being 500 per cent higher this year than last – and they might well be going up further as supply really starts to fall short of demand.

The one consolation is that they’re coming out of the higher-gas-demand winter months, so they have until later in the year before they need to be ready to face the next period of high demand.

The market expects a significant shortfall in Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG)

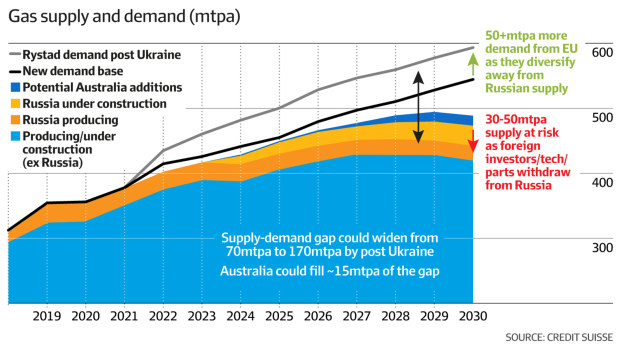

As you can see in the graph below (courtesy of the Australian Financial Review), even before the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there was going to be a widening gap between the available supply of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and global demand as this decade progresses.

Currently, the world produces about 400 million tonnes of LNG per annum, but even before the Ukraine crisis emerged, a gap of about 70 million tonnes per annum was likely to open up by 2030.

Now we have to factor in the impact of sanctions against Russia into both supply and demand, globally.

On the supply side, the anticipated degradation of existing Russian gas fields and the abandonment of planned projects as a result of Western sanctions could see somewhere between 30 and 50 million tonnes of gas lost to the market.

On the demand side, Europe will be looking for between 40 and 70 million tonnes that only a couple of months ago they were anticipating getting from Russia every year.

Where can the EU get more gas?

Saul Kavonic, Director in Credit Suisse’s Australian Research team covering Integrated Energy, Resources and Carbon markets, told the AFR that he expects the supply/demand gap to expand from 70 million tonnes per annum to about 100 million tonnes per annum.

Because there isn’t enough capacity coming online in current and planned projects, he believes that “Prices will have to rise materially to incentivise such a large wave of supply”.

The reality of rising prices is expected to lead to a coordinated global effort to solve the supply shortage and source cheap gas. If this happens, Australia has a significant part to play.

While the first ports of call for European buyers will probably be existing gas exporters such as Qatar, Algeria, and Nigeria, those exporters also supply Asian countries, as does the United States.

The US has already agreed to ship an additional 15 billion cubic metres of LNG to Europe by the end of this year, with the aim of supplying 50 billion cubic metres per year of additional gas until at least 2030.

Are we able to contribute more to the global gas market?

If Australia is to play its part in the global appetite for cheaper energy, we could ramp up supply to our nearer neighbours, thereby freeing up some of the supply from other exporters to meet those increasing EU needs.

“Australian gas could play a meaningful role in aiding European energy security, with every cargo of LNG Australia sends to Asia freeing up more affordable gas to head to Europe,” Kavonic says.

He sees the opportunity for Australia to contribute about 15 million tonnes of the supply/demand gap this decade, but he warns that there is a need for policy changes to secure what he calls “Australia’s freedom gas”.

He also suggests accelerating approvals for new LNG supply will help the cause, as will policies that encourage joint venture cooperation and help solve labour shortages in the sector. Policies that limit east coast gas exports, and hold prices down, may also need to be tweaked.

Will gas prices rise?

Buyers want cheap gas, but when demand outstrips supply of any commodity, prices tend to rise. This is because buyers will always be willing to pay more to ensure they get what they need, and the market sells to the highest bidder.

There is an old saying in the commodities market: “the cure for high prices is high prices”. Gas-producing projects requiring massive investments may have been on hold or unviable, but now have the incentive of greater earnings. Usually, elevated prices attract investment and things eventually balance out.

The unfortunate part of the equation is, of course, that this takes time. Before prices can balance and we get low energy prices again, they may go up for everyone, including those not in a good financial position to pay more.

Kavonic sees the possibility of “energy poverty and emissions concerns arising in developing countries, who are less able to afford higher gas prices, and may resort back into more coal on cost grounds”.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, several countries have also said they will have to use more coal, potentially extend the life of nuclear plants, and increase renewables output.

Whatever happens, Australia might not be able to completely “dodge the bullet” of higher gas prices, but we might find ourselves somewhat insulated (due to being isolated). In other words, even if prices do go up here, it probably won’t be as much as we see elsewhere.