A couple of weeks ago (June 11) the Australian Energy Market Commission released its final determination and rules on wholesale demand response, noting that the rules will take effect in October 2021.

This came despite some major players in the energy sector lobbying for reforms to be delayed, citing the impact of COVID-19 as a mitigating factor.

“We have considered requests to delay this reform, but we think the case for pressing forward is strongest because acting now will help keep the power system reliable and secure ahead of the 2021/22 summer,” AEMC Chief Executive Benn Barr explained in a media release.

“Despite COVID, we still need to keep prices down, keep the market working efficiently and work to lower emissions in the energy sector.”

What is demand response?

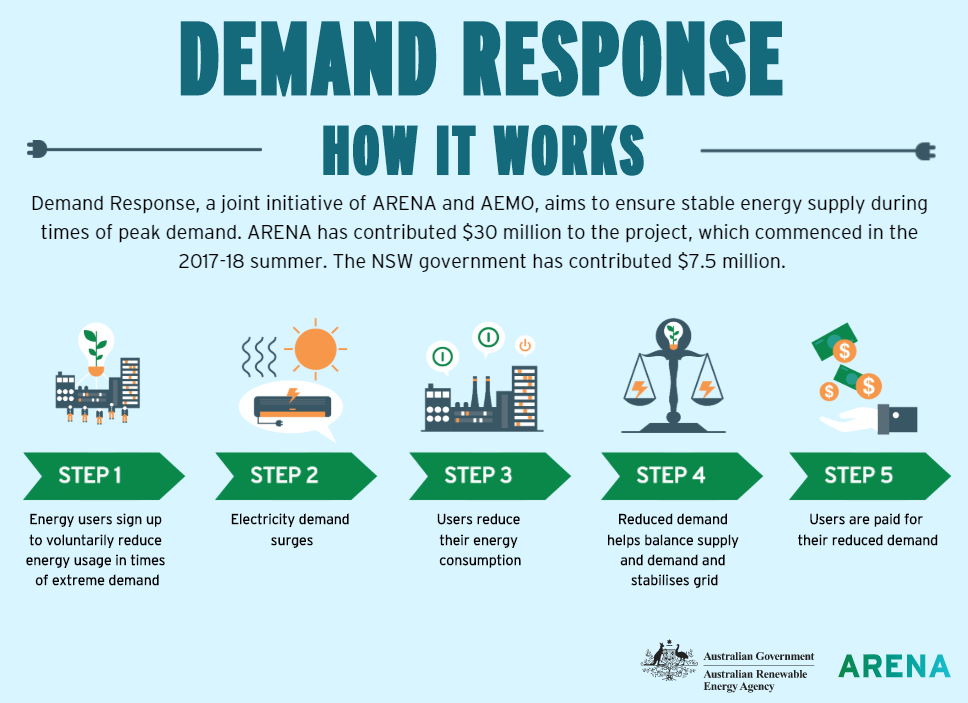

The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) gives this simple explanation:

“Demand response is the voluntary reduction or shift of electricity use by customers, which can help to keep a power grid stable by balancing its supply and demand of electricity.”

To make it even clearer, ARENA has produced this graphic:

Last year, when we asked Is demand response the answer to all our energy woes?, we included this explanation by The Australia Institute:

“Demand response has many benefits including increasing competition, reducing the cost of electricity and improving grid reliability. The International Energy Agency states that the reliability services from demand response are also valuable in managing the safe retirement of coal-fired power stations.”

It should be hard to argue against anything that results in both a more reliable grid and the reduced cost of electricity – even before you add the safe retirement of coal-fired power stations to the equation.

The basic concept

At times when the grid is under strain, some of the load on the network is less crucial than others. The commonly talked about example is to imagine what a black out can do to a nursing home, aged care facility, or medical storage site.

Then compare the impact on a factory making plastic furniture. If the factory can power down for a day, it can help keep critical infrastructure operating.

Australia is now at a point where there isn’t enough reliable supply to keep everyone online all the time.

How will demand response be implemented?

The reform, which is officially called ‘the wholesale demand response mechanism’, is designed to encourage big energy users (such as smelters and factories) to reduce their electricity consumption in response to wholesale market price signals, saving them money.

The demand will be scheduled into the market in the same way an electricity generator’s supply would be scheduled in.

As the AEMC explains, this new way of operating recognises that not using electricity should routinely attract a market value. It’s another tool to help balance energy supply and demand.

This voluntary short-term reduction in usage is potentially a much cheaper way to address sudden spikes in demand than calling on sources of peaking generation, such as gas or pumped hydro.

Barr says starting with the biggest users makes sense, but smaller users – including households with rooftop solar – will follow in due course.

“Small and large energy users respond differently so it’s more practical – and quicker – to start with the group whose demand is easiest to predict. We can also use this experience to learn valuable lessons about dispatching electricity in this new way.”

But how do you put a price on switching off?

One idea is to allow consumers to participate by actively trading their energy use. When they decide to use and not use energy impacts the supply-demand equation.

“Once the two-sided market is up and running, we can retire this wholesale demand response mechanism because it will no longer be needed,” Barr says.

“But taking a stepped approach to consumer participation in the market is cheaper, more practical, and safer for households and businesses.

“If we applied the change to both large and small consumers at once it would involve significant, complex, and costly system changes that would end up on household bills.”

Eventually the grid will benefit from the distributed cheaper energy resources used by households, such as solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles.

Meanwhile, some small consumers are already able to take part in one of the demand response trials being run by several governments and some distributors.

Will I see the benefits?

If wholesale demand response results in fewer blackouts at times that peak demand puts real pressure on the system on those extremely hot days, as we’ve seen over the past few summers, that will already be a plus.

If it also means that the cost of generating enough energy to meet demand is lower, and that trickles down to reduce the overall wholesale cost over time, then that would clearly also be a win.

What we’ll have to wait and see is whether only those households with the capacity to contribute their own energy, via solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles, receive any meaningful benefit from the two-sided market.

It is possible that this reform will result in an even more inequitable system, potentially further disadvantaging those who can least afford it, including lower-income households, pensioners, and renters, who may not be in the position to participate.

However, this is only one of the reforms that the AEMC is working on, and the fact that it has pushed ahead despite some industry opposition gives us some confidence that good intentions will result in good outcomes.