We’ve noted previously that the energy mix in Australia is changing, as greater generation and supply from renewable sources kicks in.

We won’t go over old ground as to how problematic that is for the ‘old school’ generators and suppliers, as the demand for their baseload power fluctuates significantly … other than to say that we’re still going to need those businesses to remain viable for some time so they can keep us fully powered up at all times of the day and night and in all weather conditions.

The changing mix

As explained in this piece on Renew Economy, at 1.15pm on Sunday July 21, the spot price of electricity on all the state-based grids in Australia’s main wholesale market hit zero at the very same time.

This was because there were cloudless skies and good breezes across most of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia, enough to push the share of demand being supplied by renewable sources in the National Energy Market to over 43 per cent.

As Renew Economy points out, this was only one five-minute dispatch period, and the price for that half-hour period (based on the average of six five-minute periods), was $7 per MWh in NSW and $6 per MWh in Victoria.

And it’s important to keep in mind that this was in the middle of the day on a sunny Sunday.

Storage needs to keep up

The main issue – or, as some in the industry see it, the big opportunity – is that we don’t yet have the capacity to store renewable-generated energy on a large scale.

This means no matter how much wind and/or solar power is able to be produced in ideal conditions, such as those on this sunny winter’s Sunday, we can pretty much only take advantage at that time.

As you probably know, the South Australian government is hanging its hat on being a world leader in the integration of renewable energy production, storage, and supply into the state’s mix, so it was a happy coincidence that the Office of the Premier put out a timely media release four days before the above-mentioned national renewables peak.

Premier Steven Marshall proudly announced the establishment of Australia’s first compressed air energy storage facility at Strathalbyn, about 60km southeast of Adelaide.

What is advanced compressed air energy storage (A-CAES)?

The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) announced $6 million in funding for this project back in February, with the South Australian Government’s Renewable Technology Fund chipping in a further $3 million.

The funding is to help Canadian start-up Hydrostor set up an Australian presence and what is essentially a pilot project, which will demonstrate the viability of its technology by repurposing the site of the former Angas Zinc Mine.

As ARENA’s media release explains: “The $30 million commercial demonstration project will use the existing mine to develop a below-ground air-storage cavern that uses an innovative design to achieve emissions-free energy storage.”

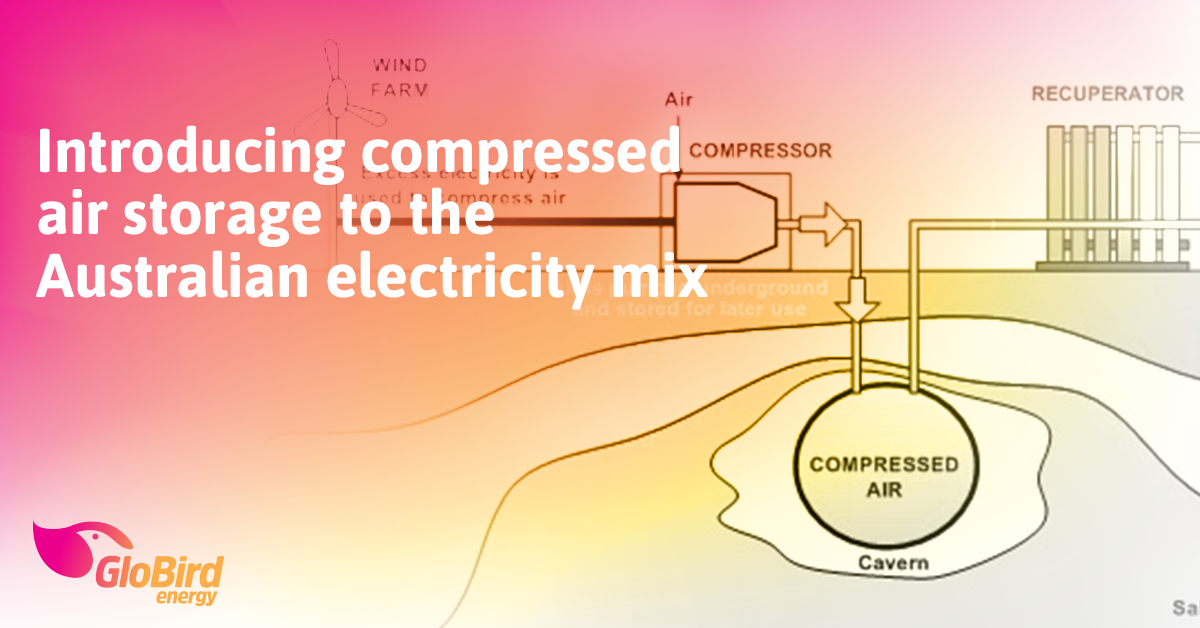

In a nutshell, the technology relies on the height difference between the energy generation system built at ground level and the compressed air storage which, in this case, will be 240 metres underground.

The air is kept under constant pressure by water above it (referred to as hydrostatic head).

During charging, heat from the compressed air is collected and stored and the cooled air displaces water up to a reservoir on the surface.

To discharge, water flows back underground, forcing air to the surface under pressure. The air is heated using the stored thermal energy and drives a turbine to generate electricity.

What’s going to happen next?

The storage market is currently dominated by lithium-ion batteries, however they’re not the best at offering very long-duration storage.

Longer-duration storage is even more valuable where a large share of wind and solar power supplies the grid (like South Australia) because of the significant fluctuations in production.

Hydrostor is starting small, partly to be able to be up and running as soon as possible (aiming for mid-2020) and partly because they need to have a showcase ‘proof of concept’ project in operation to secure the sort of investment and partnerships they need to build on a larger scale.

If Hydrostor can prove its technology in Australia’s wide-open power market, it could lay the groundwork for megaprojects of the order of hundreds of megawatts each.

Among the 15 or so sites in its global development pipeline, Hydrostor is planning 200 and 300-megawatt systems, which would easily surpass any other storage in the market.

All that means that there are plenty of eyes watching this project closely (us included).