Incentives are a wonderful thing. If you want to motivate communities for the best social outcome a very effective way to do so is to give people some ‘encouragement’.

About 20 years ago, various governments decided that encouraging Australian households to install rooftop solar would be a good thing. This essentially started the transition away from a dependence on fossil fuels and toward an increase in energy generation and usage from renewable sources.

There was clearly an appetite among Aussies to get on board. People could see that having a rooftop solar array would be a good thing.

While a good proportion of the population was eager, regardless of any incentives, some liked the financial inducement of subsidies to reduce the up-front cost of installation and feed-in tariffs that offered a financial return on the investment.

Wildly effective inducements

To say that the financial incentives of having your installation subsidised and then selling your excess energy back to the grid were effective would be an understatement.

More than 3.3 million Australian households now have a solar power system installed on their roof (according to SunWiz). There were over 300,000 installations in 2022 as November and December became two of the five biggest months on record.

Nearly 1 million of those are in Queensland, where 82% of roofs deemed suitable for solar PV now have them (surpassing the South Australian penetration rate, which is currently 78%).

Rooftop solar panels now combine for over 20 gigawatts (GW) of power capacity and pretty soon, when the Liddell coal-fired power plant is fully closed, rooftop solar will surpass coal power capacity!

Be careful what you wish for!

You could say that Australia has overachieved when it comes to household solar energy.

Homeowners collecting the sun’s abundant renewable energy and using it to power their appliances is an amazing thing that we now take for granted.

Households feeding their excess energy into the grid is also a tremendous thing – but only to a point.

It’s a great thing when other users need that readily available energy, but not such a good thing when nobody is using it. After all, the grid was never designed to cope with holding on to excess energy until it’s needed.

So, in the middle of the day when the sun is shining but demand for energy is low, there’s simply too much solar energy available. Nobody wants or needs it and there aren’t enough people with the capacity to store it for use later when the demand picks up.

A recent article in The Financial Review explained how solar panels have “resulted in a glut of cheap electricity in the middle of the day” yet there is less baseload power available when demand is high in the evening peak. This results in a significant difference in the value of energy depending on the time of day.

The Duck Curve is getting ‘duckier’

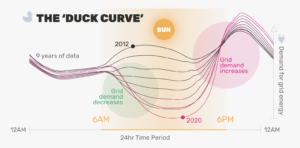

Back in the day (about 10 years ago), demand for energy from the grid used to be relatively flat across the day.

As more and more rooftop solar came into the mix, the demand on the grid in daylight hours gradually decreased, however, once the sun went down, the peak became a real spike.

Year by year, the divergence between daytime demand and evening demand has increased, as illustrated in this diagram (which borrows modelling from the Californian ‘Duck Curve’ chart).

Image is for illustrative purposes only. Data pictured is not actual*

Flattening the curve

There are two things that can help make that duck less ducky: more people using energy in the middle of the day and increased storage capacity to keep the excess solar energy out of the grid until there is demand for it.

GloBird Energy has addressed the first thing with our Free Lunch. It’s our plan to incentivise customers to run their washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, and any other “non-time-sensitive” appliances when they’re most likely being powered by renewable energy, between midday and 2 pm.

That time shifting of usage means an equivalent amount of electricity generated from non-renewable sources isn’t being ‘demanded’ after the sun goes down.

The second part of the equation relies on a greater take-up of battery storage, which has started happening.

SunWiz reports that about 15% of new solar PV installations in 2022 were combined with home storage, an increase from around 10% in 2021.

An estimated 47,100 storage systems were installed last year, equivalent to about 589MWh capacity, up over 50% on the 2021 figure of 333MWh. That brings us to around 180,000 cumulative installations with about 1,920MWh of capacity installed since 2015.

South Australian, Victorian, and ACT residents have access to subsidy programs.

Changing the patterns of both demand and supply

The amount of power you use is less important than your usage pattern. Using next to none all day but switching on all your appliances (including heating or cooling) between 6 and 10 pm puts more stress on the grid than using power at a steadier rate throughout the day.

Multiply that usage pattern out over hundreds of thousands of households and you can appreciate that steady usage is far preferable to concentrated usage spikes.

At the same time, offering excess solar-generated energy to the grid when it’s not needed doesn’t have a lot of value, but having some to feed in during times of peak demand is a lot more valuable.

Changing feed-in tariffs

To encourage those who have the capacity to feed in their excess energy at times of peak demand to help us flatten the Duck Curve, we’re introducing time-of-use feed-in tariffs.

By having three different rates, depending on the time of day and its corresponding demand level, we will reward customers who feed in at times when their energy is needed and when it supports the grid.

The reality is that it no longer makes sense to offer a single flat feed-in rate, because that could only be extremely low, and the incentive would become negligible. There would be no access to the additional value of energy at peak times.

Because we do want to encourage as many customers as possible to feed in when their excess energy is most needed – which, to a large degree, also means encouraging more households to install battery storage – we’re helping move Australia’s renewable energy transition to the next phase.

Admittedly, there will be some solar energy customers who aren’t in a position to feed in at the times they’ll receive the better rate, however, the important thing is that we are incentivising vital changes to what has become an unsustainable model.